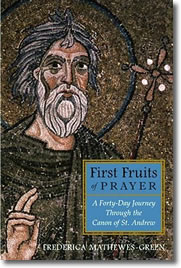

First Fruits of Prayer: A Forty-Day Journey Through the Canon of St. Andrew

by Frederica Mathewes-Green

Paraclete Press, 2006

Frederica Mathewes-Green (Facing East, The Open Door), a Beliefnet.com columnist and a commentator for National Public Radio, turns her capable pen to the Canon of St. Andrew in First Fruits of Prayer: A Forty-Day Journey Through the Canon of St. Andrew. This text, I discovered in the introduction, is a “prayerful hymn of epic length” offered during Lent each year in the Eastern Orthodox Church. “Let this hymn soak into your bones,” urges Mathewes-Green compellingly. After a lengthy introduction to the Canon of St. Andrew that includes practical ideas for usage and historical context (very helpful for non-Orthodox readers like myself), Mathewes-Green presents it divided into 40 readings.

I approached the Canon of St. Andrew as a first-time reader, and was startled by the intensity and beauty of the ancient text. It is “intense” in that Andrew does not sugar-coat sin, as do so many spirituality authors today. Rather, I bumped into lines like this:

I confess to Thee, O Savior, the sins I have committed, the wounds of my soul and body, which murderous thoughts, like thieves, have inflicted inwardly upon me.

Or another,

With my lustful desires I have formed within myself the deformity of the passions and disfigured the beauty of my mind.

This has the same effect as a bracing cold shower—you are startled awake, and see clearly the magnitude and cost of turning away from God. I’m not sure a contemporary text could get away with this in the same way.

Also helpful is the screened commentary pages that accompany each of the 40 chapters (although the small type of the commentary pages against the gray background of the screens will challenge middle-age readers who need bi-focals, like this reviewer). Without the commentary, I would have made several wrong assumptions as I read. In one place, for example, “Holy Mother Mary” is not the mother of Jesus, but St. Mary of Egypt. (A bonus is the inclusion at the end of the book of the story of St. Mary of Egypt, paraphrased and summarized by Mathewes-Green.) The commentary page ends with thoughts for consideration that lend context to the ancient wisdom, which might otherwise seem difficult or bewildering to the contemporary reader.

I particularly liked Mathewes-Green’s anticipation of how readers might feel conflicted about the text. In one portion of the commentary, she notes, “This assertion of St. Andrew that he has sinned more than any other person…(is) startling to contemporary readers.” She then gives a short explanation. After reading petitions to St. Mary of Egypt, St. Andrew, and the Theotokos, she notes in the commentary, “How do you feel….? Is their presence alongside us in prayer helpful, or intimidating, or frankly not believable?” This is disarmingly invitational for non-Orthodox readers, who might otherwise put the book down and are instead intrigued enough to continue.

There are many helpful observations as well, such as when she offers a short definition of the fire of Gehenna (“and thou, my soul, hast kindled the fire of Gehenna, and there to thy bitter sorrow thou shalt burn”). Gehenna, I learned, was a garbage pit in New Testament times in which the bodies of executed criminals were tossed. She also recaps pertinent scriptural stories that are referred to in the text that might not be generally familiar.

However, Mathewes-Green does not feel as if she has to explain everything. Many of the questions she asks are designed for personal reflection and meditation (“In what sense is your flesh an ‘idol’ to you?”) She doesn’t shy away from some of the more difficult passages, such as St. Andrew’s words dealing with Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his only child, Isaac. (Mathewes-Green asks the reader, “Think through what it would be like to sacrifice to God whatever is most precious to you, in the firm expectation that God can restore it.”)

I confess to

floundering over a few of the terms in the commentary sections (what is a

“tropation, or irmos?”) But mainly, I was struck by Mathewes-Green’s pithy prose

and talent for cutting to the heart of each reading (In one section, she

remarks, “…the temptation to consider any other person worse than yourself lays

an axe to the root of your soul.”) Mathewes-Green’s arrangement of readings from

the Canon of St. Andrew will make this ancient text accessible to readers who

might otherwise fail to tap into its beauty and wisdom.

Copyright ©2006

Cindy Crosby

Help explorefaith.org. Purchase a copy of FIRST FRUITS OF PRAYER by following this link to explorefaith.org.