Finding New Life in a Celtic Easter

Ten years ago, just two weeks after Easter, I made my first pilgrimage to Wales. The journey took me from the warm, robustly green spring of central Texas to chill and damp weather and to skies full of gray, scurrying clouds. Upon crossing from England to Wales,my first impression was that it was still winter.

Ten years ago, just two weeks after Easter, I made my first pilgrimage to Wales. The journey took me from the warm, robustly green spring of central Texas to chill and damp weather and to skies full of gray, scurrying clouds. Upon crossing from England to Wales,my first impression was that it was still winter.

The land still seemed asleep. The cold seeped into my bones. How could it be Eastertide?

Then fields of solid yellow began to appear. Daffodils! Daffodils in full bloom. Daffodils without number. Spring breaking through despite the cold. As rays of sun began to play “hide and seek” among the daffodils, the radiance of light was particularly stunning—golden yellow illumined, as if from within. At Abergavenney, the first stop on our journey, the local vicar welcomed us with cups of tea and scones, and the chill began to loose its grip on both my body and soul. Following Evening Prayer at St. Mary’s Church, one elderly woman parishioner spontaneously began reciting “The Daffodils,” by William Wordsworth, her face brimming over with laughter as the poetry poured forth. At the poem’s conclusion she beamed at us, bright blue eyes alight with joy. “Croeso. Welcome. Christ is risen!” Thus we were welcomed to Wales.

I had come to Wales in the midst of personal grief. I was weighed down by that leaden sense that nothing could be made new. It was two weeks past Easter, and I had no sense of the new creation. Not in me. Not in the world. In the six months prior to this trip, our house had been vandalized, a friend had died, my mother’s illness had worsened and my husband had just lost his job.

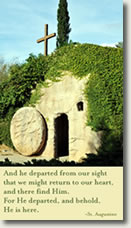

And so the daffodils and the poetry were a gift. The genuine hospitality of our Welsh hosts began to kindle the first sparks of new life; little signs of Easter fire began to run through my veins. In the first lecture given to our group by Patrick Thomas, Anglican priest and Welsh scholar, we were reminded of the emphatic proclamation from the Celtic Church that Christ lives, that our gospel tells us that God always brings life out of death. The living God revealed to us in Jesus delivers us from our own tombs again and again, hallowing our sufferings by his presence, indwelling every harrowed nook and cranny of our lives.

Patrick spoke of the confidence of the Celtic Christians—a confidence that everything comes from God, and everything returns to God. He reminded us that the history of Wales is a history of being overrun by their neighbor nation to the east. Perhaps because the survival of Welsh culture—its language, its traditions, its festivals—was at risk, resurrection is a dominant theme in Welsh spirituality. When we are faced with loss, when we are at the brink of disaster, Patrick observed, the Easter shout may be all that keeps us going. “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and to those in the tombs bestowing life.”

In a singularly emphatic manner, the tradition of prayer from the Celtic tradition of Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Brittany, Cornwall and the Isle of Man rejoices in the resurrection. Christ is living and active, walking with us every step of the way, guiding our actions, aiding our prayers. As the prayer from the Outer Hebrides puts it,

My walk this day with God,

My walk this day with Christ,

My walk this day with Spirit,

The Threefold all-kindly:

Ho! Ho! Ho! The Threefold all-kindly.

The living Lord is constantly with us, in every moment, every detail. Because Christ is with us, his resurrected life suffuses our own, breaking through when we are at our weakest. In fact, this tradition offers us a vision of creation and resurrection in which there is no separation of the two. Following the great hymn found in the first chapter of St. Paul’s letter to the Colossians, these prayers remind us that “in Christ all things hold together.” (Col. 1:18, NRSV) All that has been created is also redeemed. All that is in existence is held in the life of the Trinity, held in an eternal movement of love. In other words, the whole universe is in Christ. The whole universe is with Christ. Because the universe is in Christ, every bit of that universe participates in the pattern of dying and rising that Holy Week and Easter form in us.

The living Lord is constantly with us, in every moment, every detail. Because Christ is with us, his resurrected life suffuses our own, breaking through when we are at our weakest. In fact, this tradition offers us a vision of creation and resurrection in which there is no separation of the two. Following the great hymn found in the first chapter of St. Paul’s letter to the Colossians, these prayers remind us that “in Christ all things hold together.” (Col. 1:18, NRSV) All that has been created is also redeemed. All that is in existence is held in the life of the Trinity, held in an eternal movement of love. In other words, the whole universe is in Christ. The whole universe is with Christ. Because the universe is in Christ, every bit of that universe participates in the pattern of dying and rising that Holy Week and Easter form in us.

On our pilgrimage, we renewed our baptismal vows at the holy well of St. Issui, a local saint from that hidden Welsh valley at Patricio. Sister Cintra Pemberton, our pilgrimage leader, told us that the water from the well had been used for baptism since the 6th century. We renewed our baptisms with water fresh from its source, welling up from the earth. Recommitting ourselves to live in the power of Christ’s resurrection, we washed with the water from Christ’s own creation, faces and hands dripping with promise. Slightly stunned pilgrims regarded each other with delight and surprise. We were already becoming a little community. Barely two days had passed, and the risen life of Christ was making us into a pilgrim band. Our souls began to soak up the power of the resurrected life of Christ, just as our skin began to absorb the droplets from this holy well.

In Welsh, the ordinary word for universe is “bydysawd,” which means “that which is baptized.” All that has come into being—every particle of matter, every creature, every person, every star and planet—is encompassed in the pattern of Christ’s dying and rising. This is not completely new to us. In the Episcopal Church, at the Easter vigil, we kindle the Easter fire and prepare to baptize new Christians. Then we speak of Christ as “he who gives his light to all creation.” (Book of Common Prayer, p. 287) The Celtic Church, following the teachings of the early councils of the church, understood that this all encompassing, uncreated Light of Christ, the Light that breaks into the tombs of our hearts and the graves of our bodies, is eternally present in all times and in all places.

In fact, Euros Bowen, one modern Welsh priest and poet, was so bold as to write, “There is no resurrection where there is no earth.” Creation and resurrection go together. Creation and resurrection are held together. In the most mundane of earthly circumstances, when we least expect it, the power of God, the power to bring forth life from death, breaks through, because creation and resurrection are of a piece. The power that brings forth the protons is the same power that brings forth life from the grave.

From the Outer Hebrides, we find this expressed in a more homely way. The tradition there holds that on Easter morning, the sun dances in celebration of the resurrection of Christ. In an account recorded by Alexander Carmichael in the 19th Century, found in his Carmina Gadelica, a woman tells of climbing the highest hill on Easter morn and seeing the sun dancing in delight: “The glorious gold-bright sun was rising on the crests of the great hills, and it was changing color—green, purple, red, blood-red, intense white, and gold-white, like the glory of the God of the elements to the children of men. It was dancing up and down in exultation at the joyous resurrection of the beloved Savior of victory.” Fanciful though this may seem, the story gives us a sense of the Celtic awareness of creation and resurrection being held together in Christ. The Savior’s rising from the dead, making the whole creation new, is cause for the sun itself to rejoice.

As our pilgrimage came to an end two weeks later, I realized that the power of Christ’s resurrection had been made real and tangible to me through my time in Wales. The poetry, the walks to holy sites, and the vital sense of the living Christ offering risen life here and now had quickened my despairing spirit. Before leaving we were given a poem by another Welsh poet, Saunders Lewis. Those lines accompanied me homeward:

Cherish the dark’s obscurity

Look for the diamonds in debris,

Thank God for all His mystery

And LIVE.

Copyright ©2004 Mary Earle.

The images are of Celtic Knotwork, which is said to symbolize the flow of the life force through the cosmos, and represents the endless cycle of life: birth, death and rebirth. The images are used courtesy of Bradley W. Schenck, Copyright 1997 & 1998, http://www.webomator.com/bws.

Help explorefaith when you purchase HOLY COMPANIONS or any other item from Church Publishing, Inc., our Partner in Ministry.

Also available at amazon.com.