Father Louie and the Little Sister

At the

age of eighteen I was an agnostic half-lapsed Catholic from New Jersey. For

reasons I won’t go into here, I spent my freshman year of college at a

Christian-based institution in the Bible-belt of northern Georgia. It was my

first immersion in a fundamentalist religious culture, and as the months passed I was subjected to continued calls to

accept Jesus as my Personal Lord and Savior. I was offered a God who really

really loved me, but would at the drop of a hat send me to hell—along with

Socrates, Plato, Siddhartha Gautama, and every other human being who pre-dated

Jesus, as well as all humans since Jesus’ time who never heard of him or whose

personal relationships with him did not live up to the criteria proclaimed by my

twenty-year-old wet-behind-the-ears tormentors.

At the

age of eighteen I was an agnostic half-lapsed Catholic from New Jersey. For

reasons I won’t go into here, I spent my freshman year of college at a

Christian-based institution in the Bible-belt of northern Georgia. It was my

first immersion in a fundamentalist religious culture, and as the months passed I was subjected to continued calls to

accept Jesus as my Personal Lord and Savior. I was offered a God who really

really loved me, but would at the drop of a hat send me to hell—along with

Socrates, Plato, Siddhartha Gautama, and every other human being who pre-dated

Jesus, as well as all humans since Jesus’ time who never heard of him or whose

personal relationships with him did not live up to the criteria proclaimed by my

twenty-year-old wet-behind-the-ears tormentors.

It was enough to drive a person to drink, which would have been a more likely option if the campus had not been dry. It was enough to drive some people to Jesus (upon which occasion one would hear great rejoicing on the dorm floor, no matter the hour. Imagine being awakened at two o’clock in the morning by joyful shouts of “Dickie accepted the Lord! Dickie accepted the Lord!” Poor Dickie, I thought, finally brow-beaten into salvation). Some, who earned my envy, were able to just ignore it all and go about their secular business of getting an education.

But I had this spiritual streak in me, despite my agnostic half-lapsed Catholic state. I had never really given up on God, just on the versions of God that had been offered by priests, nuns, and, now, the post-pubescent college boys who had exclusive keys to the magic-Jesus formula. So I needed something besides stoic self-imposed exile or the occasional snuck-in shot of whiskey to get me through. What I got was initiation, at an off-campus site, into the technique of transcendental meditation.

All things considered, I’d still take the meditative state of consciousness over the fascist Jesus any day. And though the organization that promotes transcendental meditation (whatever it calls itself these days) turned out to have somewhat cult-like qualities of its own, especially for a spiritual freelancer and non-joiner such as myself, I think the interior experience it offered provided a standard for my spiritual life and outlook that remains definitive, and it opened Christianity up for me in a whole new way.

But, as Arlo Guthrie said about his long tale of getting arrested for littering on Thanksgiving, That’s not what I wanted to tell you about. . . .

I wanted to tell you about the time, about a year later, while attending a different college, much farther north, I went to a weekend residential course to learn more about the whole meditation thing. The course was given at a Catholic retreat house just outside Philadelphia, out on the Main Line—an old estate, probably willed to the Church by some good Catholic whose family had reached the end of its line. The house was run by a group of nuns who provided gracious hospitality and good food, and who didn’t seem to be worried about meditators becoming possessed by the devil owing to the simple act of quieting the mind (my fundamentalist dorm-mates the year before had worried about this expressly, and saw my subscription to the Village Voice as a clear sign of possession). It was a beautiful spring weekend and all was well in my little world.

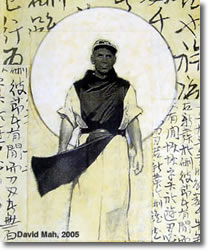

In between meetings and meditations I at one point noticed, on a table at the bottom of the main stairs, a paperback book titled The Man in the Sycamore Tree: The Good Times and Hard Life of Thomas Merton by Edward Rice. I had never heard of this Merton, but as I flipped through the book he captured my attention. He was a monk of some sort—Catholic? Buddhist? The book was filled with photos of Merton and his friends—in this one they are nattily dressed, in another, slovenly, in yet another, they appear to be seriously hung over. It included line drawings by Merton—naked women, abstract calligraphies, pictures made from words.

As I looked through the book, the diminutive sister who seemed to be the top nun on the retreat center’s totem pole walked through the foyer in which I was standing. She smiled at me and said nothing as she took note of the book in my hand. I sheepishly returned it to the table, smiled back, and continued on my way.

Later, between more meetings and meditations, I went to the main stairs again to take another look at the book about Merton. The little sister again walked by, again greeted me wordlessly, again noted the book in my hands. Later still, I went to the book rack on the landing halfway up the stairs and scoured the wire rack to see if there was a copy of the book available to buy. I saw plenty of books about St. Francis, the Blessed Virgin, the divine office, and the rosary, but no Man in the Sycamore Tree. I was ready with a dollar ninety-five to put in the honor-system cashbox, but was out of luck. I checked the rack one more time, looking behind every book to see if there was a hidden Merton to be discovered, and as I hunted, the little sister descended from the top of the stairs, greeted me again, and went on her way. I wrote down the title of the book in hopes of finding a copy when I got back home.

The next morning, when the time came to leave, I went to the book rack for one last look. Lo and behold, a copy of The Man in the Sycamore Tree presented itself. I stuffed my money into the cash slot, picked up my overnight bag and, with book in hand, walked down the stairs. On the table there was no copy of the book. I looked from the table to my hand, realized it was the selfsame book, and then saw that I was being watched by the little sister, who smiled and wordlessly bid me goodbye as I exited to begin my walk to the train station.

So that’s how the little sister made sure that my apparent desire to become acquainted with Father Louie (Merton’s monastic name was Louis) would be fulfilled.

This was back in the days before a few keystrokes on a computer could bring a person’s life to your desktop. Today there are plenty of resources (books, web sites, entire libraries) that anyone can consult to learn about Merton: his Euro-American upbringing, the deaths of his parents, his conversion to Catholicism, the many twists and turns that led eventually to a monastic vocation to a Trappist house in Kentucky, his absurd death in Bangkok. It doesn’t take long to gain an appreciation of his breadth of interest and his depth of understanding and compassion; he was an eclectic’s eclectic with an amazing knack for leaving a paper trail. It has been nearly thirty years since Father Louie and I got together with the attentive help of the little sister, and though I have delved deeply I realize that I still have far to go. With new works coming to light every few years, it is unlikely I will ever “finish” with Merton. But he was far from done himself when he met his untimely end.

In all these years I have not canonized Merton or sat awestruck at his feet or, God forbid, made him the object of “study.” I have, in a way, stayed in touch with him as if he were an old friend. Just as with actual friends, we sometimes lose touch for awhile and then enjoy a new period of intense contact. He has also been the conduit to new friends without whom my life would be less rich:

Mark Van Doren, one of Merton’s mentors at Columbia University, whose literary work, if you can find it, still rings true;

Chuang Tzu, the ancient Taoist whose stories and sayings Merton re-presented with ebullient respect;

Thich Nhat Hanh, the exiled Vietnamese Buddhist monk who continues to teach peace to millions of readers and retreatants, a man from whom I learned that you do not “strike a bell,” you “invite it to sound”;

Ad Reinhardt, the abstract painter whose black-on-black paintings will either take your breath away or leave you scratching your head—I was breathless the time I stood in a gallery with several of them;

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, the Kentucky photographer whose photos of Merton are the best ever made and whose work in general shatters norms and presents the world in a whole new way;

Robert Lax, Merton’s best friend and perhaps the most under-appreciated American poet of the twentieth century. Lax was a spirited minimalist who made words dance and whose presence, by all accounts, was that of a spiritual master.

And then there are Merton’s writings, pieces of which have traveled with me everywhere I’ve gone as the years have rolled by. Reading Merton’s autobiography, it was impossible for me to continue without stopping to re-gather myself when I came to his poem about his brother John Paul, missing in World War II:

Sweet brother, if I do not sleep

My eyes are flowers for your tomb;

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

When all the men of war are shot

And flags have fallen into dust,

Your cross and mine shall tell men still

Christ died on each, for both of us. 1

In one of Merton’s most quoted passages, he, a monk, has a deeply spiritual experience in an unlikely place. I’m glad that I can still read it as if for the first time, back before I knew there was an army of seekers hanging on and analyzing Merton’s every word.

In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. . . . 2

There is his astounding “Special Closing Prayer,” offered extemporaneously during his final journey throughout Asia.

Fill us then with love, and let us be bound together with love as we go our diverse ways, united in this one spirit which makes You present in the world, and which makes You witness to the ultimate reality that is love. Love has overcome. Love is victorious. Amen. 3

I am haunted occasionally by the beauty of single lines of his poetry that float through my consciousness context-free.

Long note one wood thrush hear him low in waste pine places 4

And these four lines say everything I need to know about the necessity of poetry.

I think poetry must

I think it must

Stay open all night

In beautiful cellars 5

In the decades since his death, Merton has been analyzed and systematized, travelogued and catalogued, synthesized and criticized and all but canonized. But the Merton who stays with me is that man in a sycamore I met by surprise on a lovely spring weekend. I take him seriously because he was flawed and raucous and even a little bit reckless. As a young man he fathered a child in London (mother and child were later killed in the Blitz). He had the kind of wild and potentially dangerous zeal that has marked converts going all the way back to Saul of Tarsus. He was as headstrong, as a monk, as he was obedient. When friends came to visit him at his hermitage he was known to knock back several cans of beer. In middle-age he fell in love with a nurse half his age while hospitalized in Louisville. He wrote and wrote and wrote. He spoke his mind and called for peace and justice, and corresponded with Pasternak and Milosz and Berrigan and Day and total strangers. He wrote a book’s worth of laugh-out-loud letters to his good pal Lax, and could just as easily riff on James Joyce as he could on John Cassian or Bernard of Clairvaux. He shot challenges at the Catholic hierarchy, and received, from Pope John XXIII, the gift of a stole the pope had worn.

My engagement with Father Louie has been a long night in a beautiful cellar, complete with art and laughter and friends and anger. It’s been the kind of friendship that could only have begun with a wordless introduction offered by a small nun to a young man on the prowl for a new sort of light.

The door’s open.

We’ll be here all night. Come on downstairs.

NOTES

1.“For My Brother, Reported Missing in Action, 1943.” See The Seven Storey Mountain, Selected Poems, or The Collected Poems.

2.“In Louisville”: See Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (page 140 in the original hardcover edition).

3. “Fill us then with love”: The Asian Journal, page 319.

4. “Long note one wood thrush”: The Geography of Lograire, page 3 (also in The Collected Poems; this is the first line a book-length experimental poem).

5. “I think poetry must”: Cables to the Ace, no. 53; also in The Collected Poems, this is another book-length poem, dedicated to Robert Lax (a.k.a. “the Ace”).

Some of Merton’s

more than 70 published works:

The Seven Storey Mountain, Seeds of

Contemplation, The Silent Life, Selected Poems, Gandhi on Non-Violence,

Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Mystics and Zen Masters, Faith and Violence,

Zen and the Birds of Appetite

Copyright ©2005 Michael Wilt